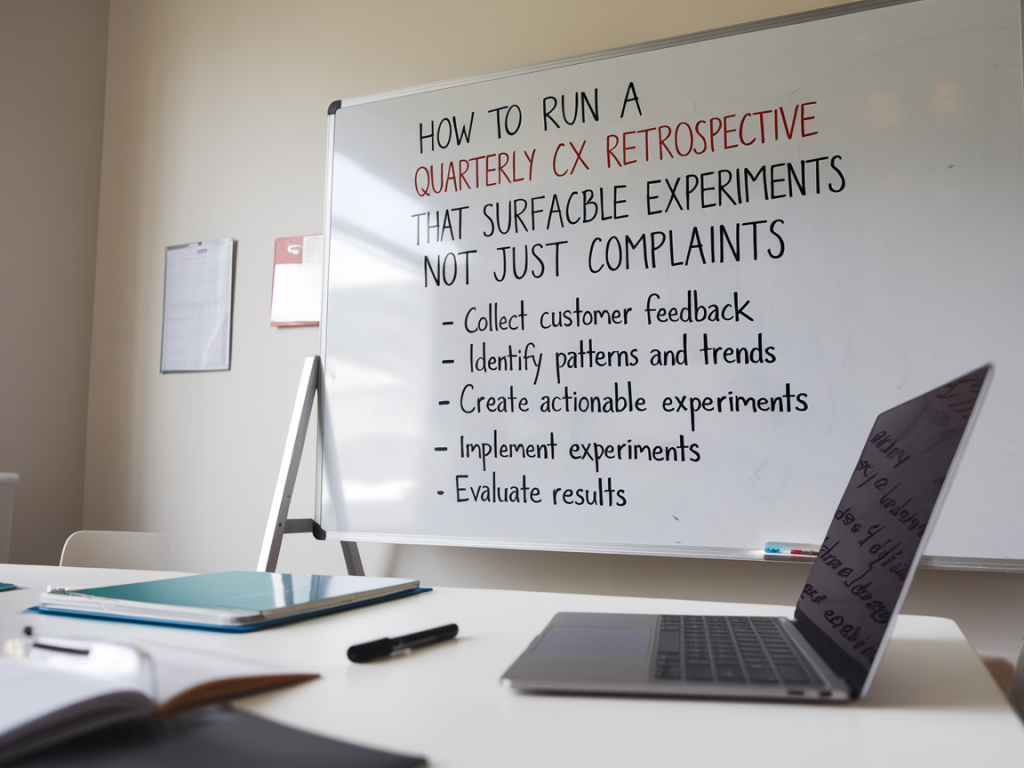

I run quarterly CX retrospectives because monthly fire-fighting and weekly stand-ups rarely create the space to learn deliberately. Over the years I’ve seen retros devolve into complaint sessions — a room where every pain point is aired but nothing changes. In this post I’ll share a reproducible template I use at Customer Carenumber Co (https://www.customer-carenumber.co.uk) to run a quarterly retrospective that consistently surfaces actionable experiments, builds cross-functional ownership, and produces measurable outcomes.

Why a quarterly cadence — and what I expect from one

Quarterly is long enough to see trends and the impact of changes, but short enough to keep momentum. My goal for each session is simple: leave with a prioritized list of experiments that are small enough to run in 4–8 weeks and tied to clear success metrics. If you finish a retrospective without experiments, you’ve created catharsis, not change.

Who should attend

In my experience the best retrospectives are cross-functional and limited in size. Invite:

- Support leads and frontline agents (2–3)

- Product manager(s) owning customer-facing features

- UX / design representative

- Data/analytics owner

- A service ops or automation specialist (chatbots, workflows)

- A customer success or account manager if your product is B2B

Keep the room to 6–10 people. If your org is larger, run mirrored sessions for each product line and a brief sync later to consolidate experiments.

Prep work — data + voices

Poor input yields poor output. I ask my analytics and support ops teams to prepare a 1–2 page brief 24–48 hours before the meeting with:

- Top 5 trends in volume, CSAT/NPS, reopen rates, and SLA breaches this quarter (visualised: charts from Looker/Tableau).

- Top 10 ticket themes by volume and time-to-resolution (from Zendesk/Intercom/Front).

- Bot & self-service performance — deflection rates, containment, and drop-off points (chatbot analytics / knowledge base analytics).

- Recent product launches or policy changes that likely affected support demand.

- Three anonymised customer quotes that capture typical sentiment.

I also ask product and UX to bring one voice-of-customer artifact: a session recording, user research snippet, or heatmap that illustrates friction. This combination keeps the conversation evidence-based and grounded in user behaviour, not just opinions.

Meeting agenda I use (2.5 hours)

I run a tightly timed session. Here’s the template I use:

- 0:00–0:10 — Opening and intent: I state the outcome we want — a prioritized backlog of 4–6 experiments with owners and metrics.

- 0:10–0:30 — Data briefing: Analytics presents the 1–2 page brief and answers quick clarifying questions.

- 0:30–0:50 — Customer stories: Read three quotes or watch a 3–4 minute recording. Brief discussion on root causes.

- 0:50–1:20 — The “Hot Spots” exercise: Each attendee silently writes 3 pain points or opportunities on sticky notes (digital equivalent: Miro). Group by theme and vote.

- 1:20–1:40 — Translate to hypotheses: For the top 6 themes, convert each into a testable hypothesis: “If we [change], then [expected outcome] measured by [metric].”

- 1:40–2:10 — Design experiments: For each hypothesis, sketch a minimally viable experiment — what we’ll do, sample size, duration, success criteria, owner.

- 2:10–2:25 — Prioritise: Use ICE scoring (Impact, Confidence, Ease) or RICE. Pick the top 4–6 experiments.

- 2:25–2:30 — Next steps: Assign owners, due dates, and the follow-up cadence (usually a 2-week check-in and an 8-week results review).

How to frame hypotheses so they lead to experiments

I insist on hypotheses that are measurable and time-bounded. A weak hypothesis looks like: “We should improve our onboarding docs.” A strong one looks like: “If we add a searchable step-by-step onboarding article and surface it in the signup flow, then deflection for onboarding tickets will increase from 10% to 25% in 6 weeks, measured by article views and ticket volume.”

The difference is specificity: change, expected outcome, metric, timeframe. That specificity lets you design a small, iterative test rather than an open-ended project.

Experiment examples I’ve run

To make this concrete, here are experiments that came from retros I ran:

- Inline knowledge check in the signup flow — added a “Did this help?” micro-question after a key step. Result: 18% increase in self-serve completion, 12% drop in related tickets.

- Two-hour SLA for billing escalations — rerouted billing issues to a dedicated queue and added a short script for common resolutions. Result: CSAT for billing rose 0.4 points; repeat contact reduced 22%.

- Chatbot fallback message redesign — instead of “I don’t understand”, the bot offered three quick options and a transcript option. Result: containment improved 9% and handoffs to agents were faster.

Prioritisation: keep experiments small and diverse

I aim for a mix of experiments: one product change, one support workflow tweak, one self-service improvement, one measurement/analytics fix. Different levers move different metrics. Use ICE or RICE scoring to make trade-offs visible. I also cap effort so that no experiment is estimated to take more than 3 sprints of work — if it will, break it down into a smaller testable step.

Ownership, tracking, and governance

Every experiment needs an owner and a place to live. I use Jira for tracking engineering/UX tasks and Notion or Confluence for the experiment log. The fields I capture:

- Hypothesis

- Primary metric(s) and secondary metrics

- Owner

- Start & end date

- Sample size / rollout plan

- Result & learnings

I insist on publishing results within two weeks after an experiment ends. Nothing kills momentum like a backlog of undocumented wins or failures.

How to measure success (and avoid vanity metrics)

Pick one primary metric per experiment tied to customer impact: ticket volume, containment rate, CSAT, time to resolution, conversion, churn risk signals. Supplement with qualitative signals (agent feedback, user quotes). If your analytics stack includes Amplitude or Mixpanel, instrument the event and build a small report before you start. If you rely on support platform exports, define the query now — otherwise you’ll waste weeks chasing the data.

Common traps and how I avoid them

Trap: “We don’t have time for experiments.” Counter: carve out one 20% sprint slice or pair product with support for a thin experiment.

Trap: “Every problem needs a big project.” Counter: require a minimally viable test for every proposed project; only escalate truly cross-cutting work.

Trap: “Retros become gripe sessions.” Counter: enforce the agenda, require a hypothesis for every pain point, and end with owners and dates.

Follow-up cadence

I run brief 20–30 minute check-ins every two weeks for active experiments and a results review 1–2 weeks after each experiment completes. At the next quarterly retrospective we review the experiment log: wins are documented as playbook steps, failed tests are annotated with learnings, and high-confidence wins are scaled or rolled into product backlogs.

Running a quarterly CX retrospective that produces experiments takes discipline: preparation, cross-functional attendance, hypothesis-driven thinking, and a ruthless focus on ownership and measurement. When you get the process right you’ll replace complaint sessions with a pipeline of validated changes that actually move your metrics — and that’s the point.